- Behind the scenes at Usborne

Why books must challenge children – Geraldine McCaughrean, winner of the CILIP Carnegie Medal 2018

Geraldine McCaughrean won the CILIP Carnegie Medal 2018 for Where the World Ends, exactly 30 years after she first won this prestigious children's literature prize. In her winning speech she calls for children to be challenged by words as well as issues in the books they read.

"Anne Fine says you must never start a speech with ‘I’ – which makes it difficult to express the sheer delight of being here, holding this award. But she’s right, because it is a communal effort that brings any book into existence. Where the World Ends was much improved by good editing, beautifully designed and illustrated, noised abroad, vetted by ornithologists and linguists, husband and daughter, accepted by bookshops, reviewed by journalists...

It only exists because real men and boys lived through a nightmare, never thinking to have their suffering exploited (or remembered) three centuries later. And of course, as Ursula le Guin said, 'The unread story is... little black marks on wood pulp. The reader, reading it, makes it live.' Thank you, readers, for breathing life into our books.

My bit always seems the easiest. It’s not the same for all writers, I know, but for me writing is one immense pleasure – a delectable, selfish, satisfying, frustrating, absorbing handicraft, like quilting – very like quilting, in fact.

Increasingly, writers-for-young-people are looked to to tackle the world’s dilemmas – which is a lot to ask, you’ll admit. But this year in particular, authors much braver than I have been prepared to wall themselves up in gruelling interior worlds to bring us books that give a true insight into injustice, impending danger, other people’s lives and hardships....

Their stories stick like burrs and won’t be shaken off any time soon. Fiction can achieve marvellous things, especially inside individual heads, not least when it subtly nudge-nudge-nudges the reader towards minding more, thinking more, asking questions.

I realise that the book industry is not the product of a single brain, but to me a very odd rift seems to have opened up. Clearly, it’s at last okay to tackle (with older readers anyway) any subject at all, however harrowing, taboo, difficult or controversial... But just as that became possible...censorship turned all its guns on WORDS. Vocabulary must not be too challenging. Books will not be published unless they use accessible language.

Accessible language is, to me, a euphemism for something desperate. Most of its tyrannies are brought to bear on younger books right now. But blink twice and today’s junior school readers will be in secondary school, armed only with a pocketful of single syllable words, and with brains far less receptive to the acquisition of vocabulary than when they were three or seven or nine...

A stac in St Kilda. Image credit: Andrew Gourley

We master words by meeting them, not by avoiding them. The only way to make books – and knowledge – accessible is to give children the necessary words. And how has that always been done? By adult conversation and reading.

Since when has one generation EVER doubted and pitied the next so much that it decides not to burden them with the full package of the English language but to feed them only a restricted diet, like poorly patients, of simple words. 'Look: We’re not going to trouble you with too many words, dear, until you have enough vocabulary to understand them.' That puts me in mind of the notice in the post office that said, 'Pencils will not be provided until the public stop taking them away'.

Worst and most wicked outcome of all would be that we deliberately and wantonly create an underclass of citizens with a small but functional vocabulary: easy to manipulate and lacking in the means to reason their way out of subjugation, because you need words to be able to think for yourself.

Forgive the strength of feeling: it comes of disgust at my failing memory. It takes me ten times as long these days to write a page of script, as I rifle through my brain for words I know exist but can’t find. That’s okay. It’s an age thing. It happens. At least, in the past I’ve walked through orchards of words, like Andrew Marvell among the nectarines and curious peaches. I’ve heard in my head (as I read them) sentences that rolled like deep ocean, and met with metaphors that turned prose into pictures.

It’s tough to lose words...but never to have even MET them in the first place? Never to have had kind parents and teachers deliver them to your door like a truck load of lego bricks – to build your very own thoughts and hopes out of? How terrible would that be? To have only enough to get by on?

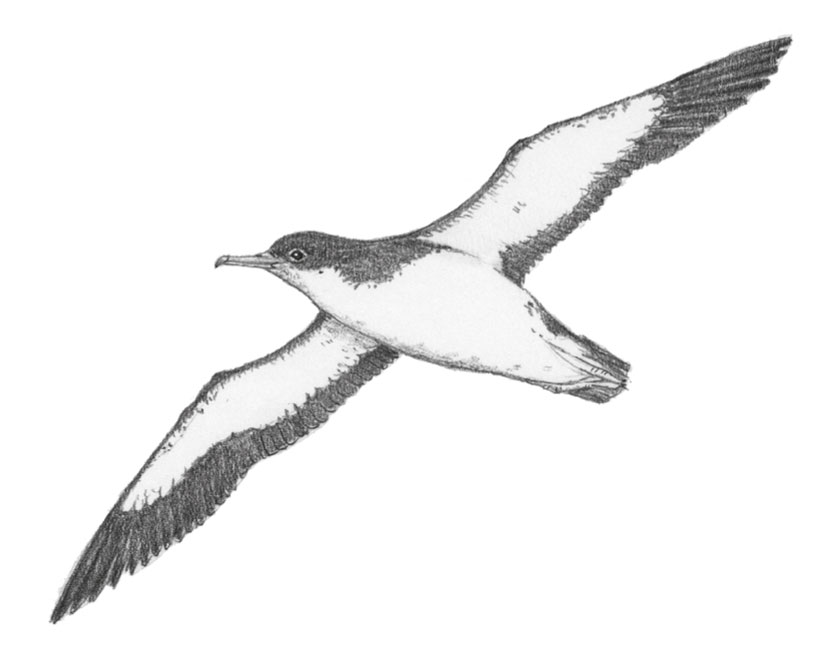

A Manx Shearwater, featured in Where the World Ends

In my opinion, young readers should be bombarded with words like gamma rays, steeped in words like pot plants stood in water, pelted with them like confetti, fed on them like alphabetti spaghetti, given Hamlet’s last retort: 'Words. Words. Words.'

So one thing makes me happier than anything else today – apart from this ‘ticket-of-leave’ to go on calling myself an author. It’s the impression I get from the whole shortlist – that the gloomy prophecies haven’t come true.

Research has been saying for years that ‘literary children’s books’ will soon be as extinct as the dinosaurs. But look! The Carnegie says that we’re still allowed to use interesting vocabulary and architectural sentences and parcel up our stories as stylishly as possible and not be banished for it."