- Tips and expert advice

Why Frankenstein is so relevant today

Mary Sebag-Montefiore, who adapted Frankenstein for the Usborne Reading Programme, explains how this classic story was written in turbulent times, and why the message is still relevant today.

I have such a fun, dream job; I condense huge fat tomes of gripping classics into something more digestible for young readers. It is a massive joy to me to bring nineteenth century literature - books that seethe with plots, emotions, tragedies, and hope – books that form the bedrock of our literary landscape and history – to receptive minds. Titles include lots of Dickens, War and Peace, Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, Don Quixote, Les Miserables… I am lit up by the wish to inspire a whole new generation to be familiar with their riches.

Mary Sebag-Montefiore

So. Frankenstein.

It is an extraordinary, powerful, haunting book. Especially when you consider it was written by a girl of 18, in 1818, when nicely brought-up girls were ideally niminy-piminy misses, and teenagers knew little of the world.

Not like its author. Mary Shelley led a rackety life that even today parents might blink at. Her father was William Godwin, philosopher, whose house was full of stars like the poets Shelley and Coleridge. Her mother was Mary Wollstonecraft, the brilliant early feminist, who wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792). She died in agony of sepsis, 10 days after Mary’s birth. In those days, doctors and midwives didn’t necessarily wash their hands.

Mary was a precocious, literary child. She disliked her stepmother; fell in love with Shelley, telling him so by her mother’s grave, and eloped with him aged 16. Shelley was already married, a father with another on the way. He believed in free love – not much fun for a faithful wife. The runaways, perpetually poor, fetched up at Lake Geneva, where the poet Byron had rented a house. There they all were, a coterie of friends and lovers, unable to go outside, the bright summer darkened by sunless, stormy skies after the eruption of a faraway volcano.

“We will each write a ghost story,” said Byron.

Thus the genesis of Frankenstein.

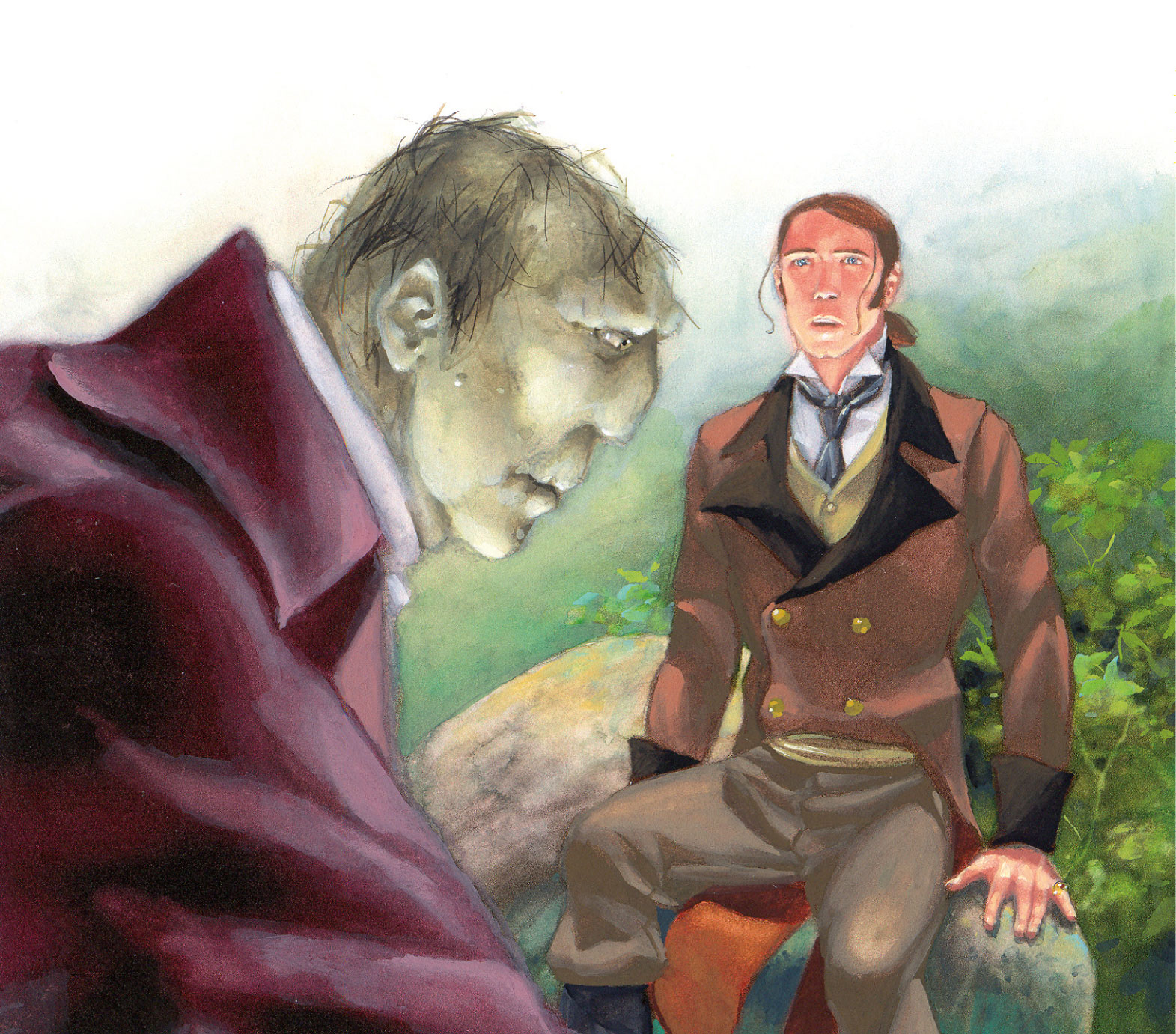

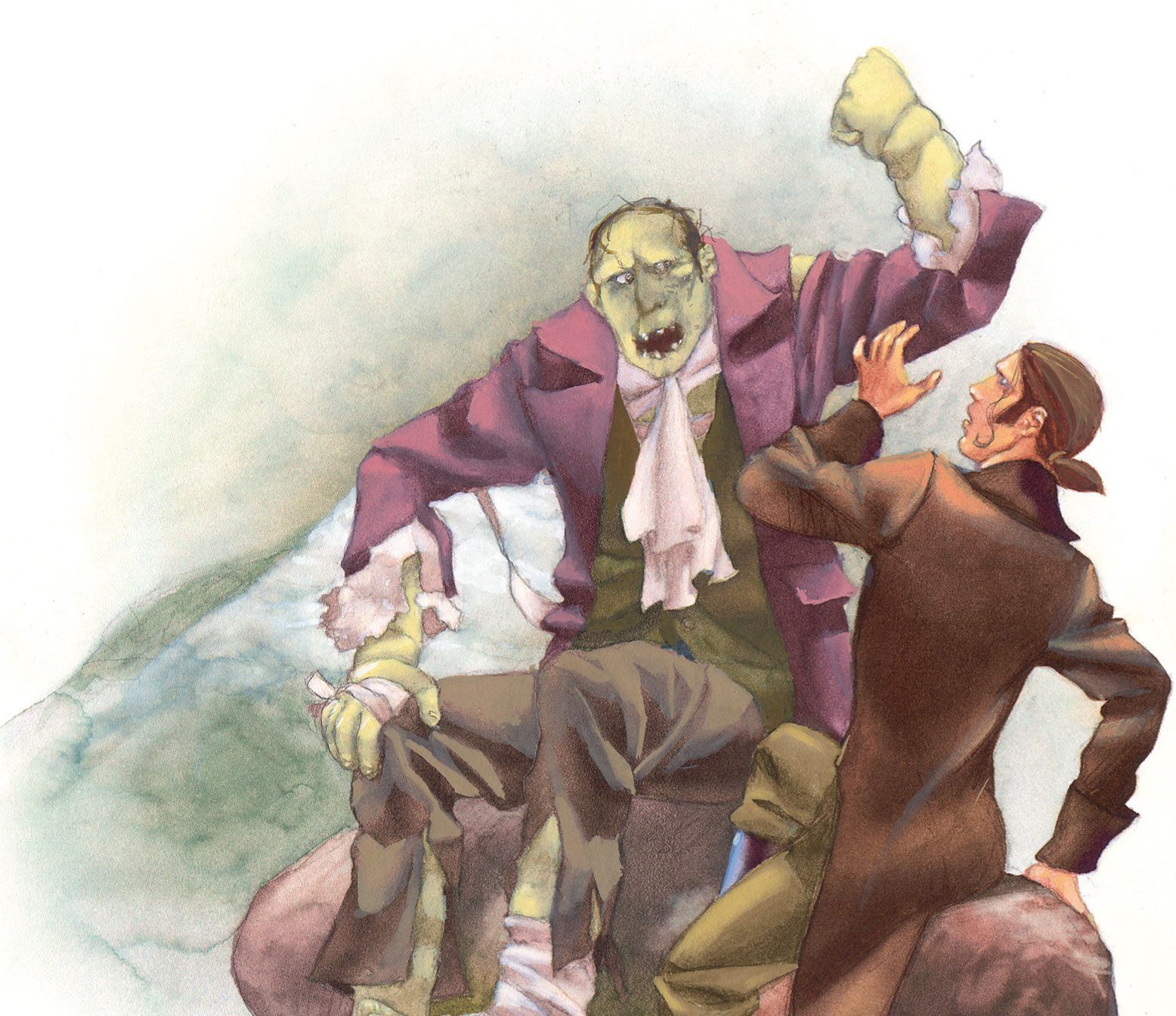

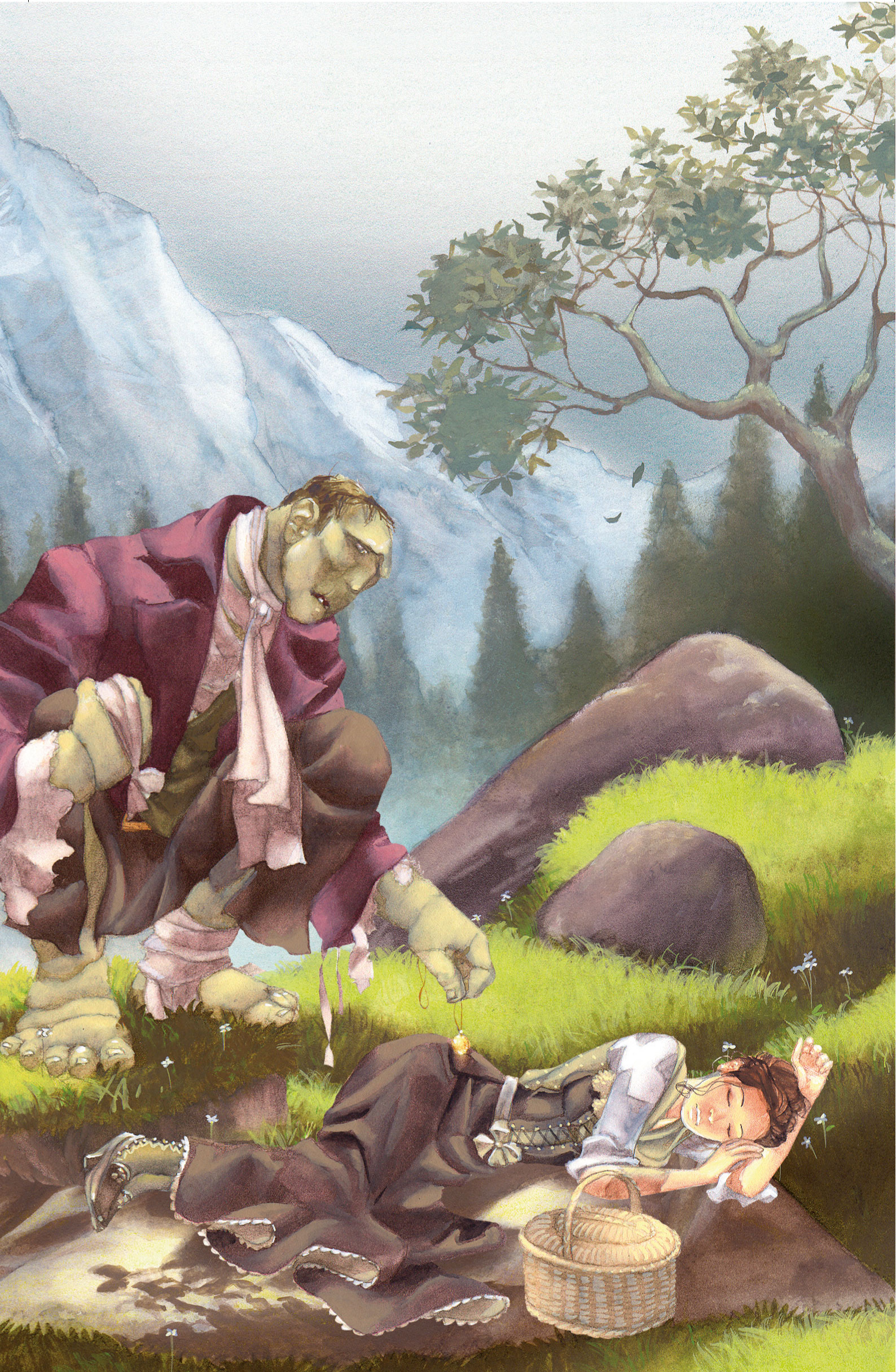

It’s the tale of Dr Frankenstein who hacks together a creature made from dead body parts, and brings it to life. He wants his creature to be beautiful; he sees himself God-like, fired with the power and glory of creation. Maybe he’ll make a whole race! But in fact he’s made a monster, hideous, huge, with skin that scarcely covers its muscle, and when it opens its awful dull yellow eyes, Frankenstein runs away in horror. The monster follows. It’s murderous. It kills everyone Frankenstein loves: his little brother, his friend, his wife, with other deaths trailing in their wake.

WHY?

The answer is simple.

"You made me," says the monster. "All I ever wanted was your love. Or at least acceptance. But I am so ugly that everyone flees in disgust. I’m lonely, an outcast, hated. So I take my revenge. I destroy. I have learnt, in the absence of love, how to hate."

Oh the relevance of this story today! Our world is bursting with new discoveries: the internet, speed of communication, hacking, artificial intelligence, advances in medical science. Exciting times! Who can foresee the consequences? The dangers? It’s beyond our understanding, the effect on our future. Frankenstein was in love with himself as the progenitor of power. Beware, says the book, of this delicious lust, or disaster and destruction will surely follow.

The monster felt rejected by society. He tried to make friends but he was cast out. Rage and despair overtook him. “The feelings of kindness and gentleness which I had entertained but a few moments before gave place to hellish rage and gnashing of teeth. Inflamed…I vowed eternal hatred and vengeance to all mankind.” The killing spree began.

Relevence again. We should beware of anyone feeling rejected or different. There is a link between mental health issues and the feeling of being outcast. The cruel yet understandable consequences of difference, driven to the monster’s extremes, are too dreadful to contemplate.

Mary Shelley’s life was never easy. Shelley drowned, aged 29. All Mary’s children died when they were little except one, Percy. She was a single, clever, loving mother, doing well, publishing her own works, paying for Percy’s education, editing Shelley’s poems, setting them before the public.

Her last years were a contrast to her beginnings. She lived with Percy and his wife, still with little money, but ensconced in a cosy domesticity that she’d never known before. Meanwhile her creative juices dried up. She published nothing for the last seven years of her life. We don’t know if she was any happier for not writing, but maybe the final message of Frankenstein is this: the kindness and loyalty of family is, in the end, the only thing that matters.

While Mary Sebag-Montefiore's Frankenstein is now out of print, you can still purchase a copy of Rosie Dickins' Frankenstein, which is part of the Usborne Reading Programme.

See all titles adapted by Mary Sebag-Montefiore, including War and Peace.

About the Author

Mary Sebag-Montefiore is a best-selling children's author, whose re-tellings of classics have been published all over the world. She is the author of over 25 books and has adapted everything from Dickens to 'War and Peace'. She has also published articles on children's books academically and in the national press, and for adults, has written 'Women Writers of Children's Classics'.

"Mary Sebag-Montefiore's retellings are perhaps the best - well-written and dramatic"

The Telegraph